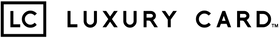

Haystack at Giverny, 1855 Scala / Art Resource, NY

Finding the Light

CLAUDE MONET’s luminous pictures of the French countryside offer a welcome armchair escape.

What is it about Monet? Over his 60-year career, the artist produced more than 2,000 oil paintings, most of which are prized works of French Impressionism in major museums. The mass appeal of his art makes his exhibitions box-office gold, guaranteeing booming attendance and gift shop sales—from posters to umbrellas to flasks with water lily–shaped caps.

Plutocrats pledge vast sums to take home an original. Last year, Meules (1890), meaning “Grainstacks,” sold at auction for $110.7 million. Another painting from the same series changed hands in 2016 for $81.4 million and in 2018 a water lily painting fetched $84.7 million—prices in the upper strata of the investment-grade art market.

Monet (1840–1926) and his contemporaries invented French Impressionism, with its characteristic evanescent effects that capture light and atmosphere. These optical “impressions” gave the movement its name. Up close the canvases are fields of flickering brushstrokes and dazzling color juxtapositions. Step back and the individual dabs coalesce to reveal a coherent, seemingly glowing scene. Is this his brilliance? The brushstroke technique? The use of color? The magical effect?

Another consideration should be the accessibility and congeniality of his subject matter. Outdoor excursions to the French countryside are well-liked by the masses, and a Monet painting offers a vicarious sense of that refreshment. At a time of industrial and urban development, Monet painted in and around rural enclaves along the Seine—Argenteuil, Vétheuil, Giverny, and the ports of Le Havre and Honfleur, where the river empties into the channel. He worked in Paris, London, and Venice, but his painted world is largely a record of day trips to the French countryside, from the suburbs of the capital to the coasts of Normandy and the Riviera.

The quintessential Monet locale is the garden that he created in Giverny, a village 45 miles northwest of Paris where he spent the second half of his 86 years. An avid horticulturist, he and his assistants planted acres of flowers and routed a stream to create the water lily pond that became the focus of his late work. “I have always loved sky and water, leaves and flowers. I found them in abundance in my little pond,” he said. The house, studio, and replanted gardens remain a pilgrimage site for art lovers.

Monet may hold the reputation of an old master, but he worked well into the modern era, long after the advent of Cubism, abstraction, and Surrealism. There is even a record of him on film in 1922, talking with a visitor to Giverny, strolling through his garden and working on a large canvas set under an umbrella beside his water lily pond. Heavyset, wearing a white linen suit and straw hat, a cigarette poking from his long white beard, he gazes across the pond. With a brush he takes pigment from his palette, glances back at the pond, and adds touches to his work in progress, repeating the process before looking into the camera.

By then Monet was revered as the greatest painter in France, but success came after years of poverty and personal trials.

Le Boulevard de Pontoise à Argenteuil, 1875 Bridgeman-Giraudon / Art Resource, NY

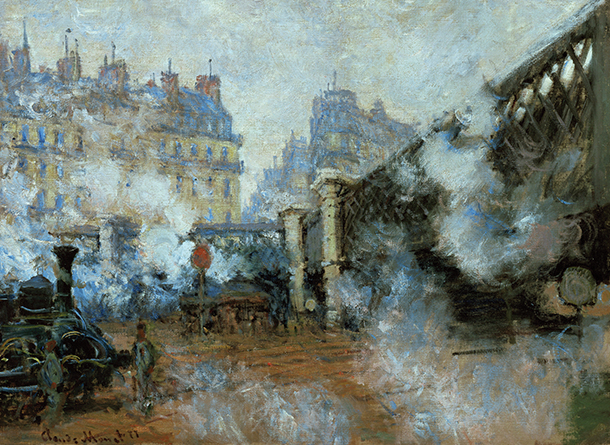

Le Pont de l’Europe. Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877 Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

ROCKY BEGINNINGS

Born in Paris in 1840, Monet grew up in Le Havre where his father sold ship supplies and groceries. In his teens he was drawing caricatures of locals and selling them in a framer’s shop. An older painter, Eugène Boudin, took Monet under his wing and introduced him to oil painting outdoors. After his mother died in 1857, he was sent to live with a widowed aunt who supported his artistic ambition and helped send him to Paris. At 21 he was drafted and sent to Algiers where his seven-year tour was cut short by a bout of typhoid. Back in Paris he studied with Swiss artist Charles Gleyre and roomed with his classmate Pierre-Auguste Renoir, one of the young artists (along with his friend Frédéric Bazille) who would join him in founding the Impressionists.

He submitted figure paintings to the official Salon, the annual state-run exhibition organized by the French Academy of Fine Arts, but most were rejected and he was unable to earn a living. A stipend from his family ended when a relationship with his model Camille Doncieux led to the birth of their son Jean in 1867. After moving to a village where they were evicted from an inn for nonpayment, Monet wrote to Bazille, “I was so upset yesterday that I did a very stupid thing and threw myself into the water; fortunately, no harm came of it.” He later reported that Renoir “brought us bread from his home so that we would not starve.”

Despite these travails, he was painting scenes of leisure and well-being. The sun-raked Garden at Sainte-Adresse (1867) shows his father with fashionably dressed figures—likely members of his extended family who had a nearby villa—relaxing on a seaside terrace overlooking the channel. At a weekend resort outside Paris, he and Renoir worked side by side painting a view onto the Seine that features row boats, swimmers, and a little island where vacationers gather. Monet’s canvas La Grenouillère (1869) depicts figures with a few short strokes and lavishes attention on the broken reflections playing across the rippled water, evoked by dashes of color corresponding to sky, clouds, and trees on the opposite shore.

Monet married Camille in 1870 and left for London to avoid serving in the Franco-Prussian War. When he returned to France the following year, after a stay in Holland, an economic boom enabled his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel to sell paintings for substantial sums. Monet and Camille rented a house in Argenteuil, 15 minutes by train from Paris. He bought a flat-bottomed fishing boat and outfitted it for painting on the Seine, and made idyllic canvases of the area, including Poppy Field (1873) in which Camille and Jean stroll among the scarlet blooms on a verdant hillside. The effect is ravishing, but loose brushwork and casual subject matter were everything the Academy reviled.

Boulevard des Capucines, 1873–1874 Album / Art Resource, NY

BREAK WITH TRADITION

Since its founding in the 17th century, the Academy trained artists to paint in sharp focus and to conceal their brushstrokes. They were expected to compose idealized scenes of historical, mythological, and religious subjects imbued with political and moralizing themes. Portraits, still lifes, and landscapes were deemed minor genres. Monet and his generation were committed instead to inventing new techniques to express their experience of everyday life.

A coterie that included Monet, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, Gustave Caillebotte, Renoir, Bazille, and others formed a Society of Independent Artists to mount exhibitions apart from the Salon. At the first of these shows, the title of one of Monet’s Le Havre seascapes, Impression, Sunrise (1872), gave rise to the group’s name when a reviewer, critical of the unfinished look of the pictures, dubbed the artists mere “impressionists.” The independents embraced the label and from 1874 to 1886 held eight “Impressionist” exhibitions. Few works sold, but the group gained notoriety as leaders of a new and vital tendency in art.

Monet’s financial security had evaporated and in 1878 he and his family moved to Vétheuil, where they shared a house with Ernest and Alice Hoschedé and their six children. Hoschedé, a wealthy collector who owned some of Monet’s works, had fallen on hard times. Camille contracted tuberculosis and weakened while pregnant with their second son, Michel. Soon after the birth, she died at age 32. Monet fell into a depression and Alice brought his children to Paris and raised them alongside her own. Her husband had moved to Belgium to escape creditors and she returned to live with Monet. In 1883, they rented an abandoned cider farm in Giverny and in 1890 purchased the property. Two years later, after the death of her husband, she and Monet married.

The Seine at Vétheuil, 1879 HIP / Art Resource, NY

SERIES PAINTINGS

In the 1880s Monet’s dealer began showing his paintings in New York. American financiers and industrialists scooped up his works and the painter began to establish his fortune. He made painting trips to Normandy, the Mediterranean coast, London, and Venice, increasingly interested in capturing the effects of different light and weather conditions. He was after what he called “instantaneity, above all the envelope, the same light suffused everywhere.” This led him by the end of the decade to make multiple variations on the same motifs. He would surround himself with many canvases, changing from one to the next as the light changed, then spend months refining them in the studio.

These “series paintings” include the grainstacks in a field near his home, which he captured aglow in orange, late-afternoon sun and bathed in blue shadow in winter. He found another subject in the poplars that lined the banks of the nearby Epte River. When the town sold the trees to a wood merchant, Monet worked out a deal with him to leave them standing until he finished his project. In the winter of 1892–1893 he rented a second-floor room facing the Rouen Cathedral and painted its façade at different times of day. Less interested in the architecture than in the light that dissolved its massive form, he described the façade’s relief with tonal modulations of pale blue and pink, applying matte pigment in small splotches that build up a scumbled incrustation as dense as the masonry of the cathedral.

A writer accompanied Monet one day in 1897 as he set out to work on his serene series, Mornings on the Seine. He would put on a white sweater, hunting boots, and a beat-up brown felt hat and walk through his garden, across the street past the water lily pond and out to the Seine, where he rowed out to his moored studio boat. A gardener would help him arrange more than a dozen canvases that he would work on as the day began. His prospect was across a lazy part of the river toward a distant shore whose trees and shrubs are mirrored in the water. A mist hangs on the river and Monet dissolves the forms in delicate puffs of lavender, mauve, pale blue, and green. The horizontally symmetrical compositions could almost be flipped without loss of readability.

Around 1898–1899, Monet stayed in the Savoy Hotel in London and from his balcony painted fog-shrouded views of Charing Cross Bridge and Waterloo Bridge. In the afternoon he crossed the Thames and painted the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Bridge at sunset. The structures hover in bluish fog or ochre coal smoke, the diffused images an homage to the atmospherics of British master Joseph Mallord William Turner and the American ex-patriate James Whistler.

Monet intended his series to be exhibited and purchased as ensembles, and throughout the 1890s he exhibited them as groups. “The desired effect can only be produced by displaying them all together,” he told his dealer, yet they were sold to disparate collectors. They still proved among his most commercially successful works and remain among his most celebrated.

Water Lilies, 1916 HIP / Art Resource, NY

WHERE THE GARDEN GROWS

By the end of the century, Monet had turned largely to the private world of his garden. He nurtured a fantasy of botanical splendor and color, laying out rectangular beds of roses, geraniums, peonies, irises, dahlias, and dozens of other species planned to change with the seasons. He built trellises and rose-covered arches, ringed the lily pond with willows, bamboo, and grasses, and built the arched bridge inspired by models in the Japanese woodblock prints that he collected. The sanctuary required a team of workmen to maintain. “My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece,” he later said.

The painter’s growing commercial success enabled him to support a household with servants and gardeners. He maintained a strict schedule, waking before dawn and heading out to paint, or working indoors if the weather was unsuitable. Meals took place at precisely the same time daily. He delighted in gastronomy and had his cooks prepare elaborate multicourse dinners, often with guests in attendance. Everything revolved around his work, which now focused on the water lilies. A 1909 exhibit of 48 of his ethereal “landscapes of water” enchanted critics and he became regarded as France’s greatest contemporary artist.

Even still, the remainder of his life would be a mix of triumph and tragedy. A flood destroyed much of his garden in 1910, and when Alice, his partner for more than three decades, died the following year, he nearly stopped painting. His elder son suffered a stroke, one of his stepdaughters died, and Monet discovered that he was losing vision in both eyes. Cataracts caused blurriness and color distortion that forced him to select paints by reading the labels. (He would not undergo an operation until 1923, when he was nearly blind.) In 1914 his son Jean died prematurely and the nation plunged into a war that would bring armies within 40 miles of his retreat.

That year he started the mural-sized water lily paintings that would become his final project. He built a large studio capable of housing the giant canvases, with a pulley system that enabled him to move them around. Between 1914 and his death from lung disease in 1926, working mostly in secret, he painted more than 100 canvases.

A group of them formed the enthralling installation tucked away in the Paris museum known as the Orangerie. The former royal greenhouse in the Tuileries Gardens showcases works by Cézanne, Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani, and Soutine, among others, but its incomparable highlight is the cycle of Water Lilies paintings that Monet gifted to the nation to commemorate the First World War. In two skylit, oval-shaped galleries—designed by the artist himself—canvases measuring 6 feet tall and together more than 100 yards in length scroll along the curving walls, creating a wraparound installation that immerses the viewer in the shady atmosphere of Monet’s water garden.

Loosely modeled on 19th-century painted panoramas that transported Europeans to foreign cities and historic battlefields, Monet designed his all-encompassing environment for purely aesthetic purposes. He made more than 250 paintings of water lilies in the last two decades of his life, but no individual canvas has such a powerful sensory effect. This tranquil, secular sanctuary—once referred to as “the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism”—is one of the greatest treasures of French art.

The Great Willow at Giverny, 1918 Bridgeman-Giraudon / Art Resource, NY

LEGACY

Impressionism was a late-19th-century phenomenon, but Monet’s career overlapped with the advent of Cubism, abstraction, Surrealism, and even the conceptual antics of Marcel Duchamp (the Dadaist who in 1917 exhibited a urinal as a work of art). In his late works Monet veered toward abstraction in which naturalistic elements are almost incidental to the overall fields of color. These works, some massive in scale, were deemed the sad result of his failing eyesight and after his death they were ignored for decades. Only in the 1950s, when their influence on the Abstract Expressionists led the Museum of Modern Art to purchase large water lily paintings, was their significance as progenitors of 20th-century abstraction finally recognized. The second generation of Abstract Expressionists—Philip Guston, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Sam Francis—became known as Abstract Impressionists. Charles Stuckey, who curated an important retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1995, wrote, “Monet’s water lilies deserve to be recognized not merely as the culmination of 19th-century Impressionism, but also as revolutionary 20th-century works, unsurpassed in their persistent and wide-ranging influence on the visual language of our century.”

Bridge at Argenteuil, 1874 Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

MONET ON VIEW

Monet and Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago

(through January 18, 2021)

More than 70 works, including drawings as well as canvases, reveal the city’s passion for Monet, from an 1888 gallery show to patrons Bertha and Potter Palmer buying 20 paintings in 1891, to the Art Institute hosting the artist’s first US museum solo show in 1895. artic.edu

Monet and the Impressionists: Masterpieces from the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris Palazzo Albergati, Bologna, Italy

(through February 2021)

Showing 57 works on loan from the Museum Marmottan Monet in Paris. The partnership is unprecedented, as this body of paintings has not been displayed elsewhere since the museum’s founding in 1934. palazzoalbergati.com

Monet at Étretat, Seattle Art Museum

(May 6, 2021–August 29, 2021)

Monet painted more than 80 works depicting the cliffs off the coast of Étretat in Normandy. Eleven of them are gathered here along with photographs, postcards, and related pictures by other artists. seattleartmuseum.org

Impressionist Decorations: The Birth of Modern Décor, National Gallery, London

(September 11, 2021–January 9, 2022)

Aside from canvases, the Impressionists made or designed decorative panels—including Monet’s large water lilies—tapestries, ceramics, fans, and other objects, which are the focus of this exhibition that premiered at the Musée d’Orsay this summer. nationalgallery.org.uk

Impressionism: The Hasso Plattner Collection, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany

(from September 5)

Among 100 Impressionist and modern works there are 34 Monets (Europe’s largest holdings outside of Paris), including a spectacular sunset Grainstacks (1890) and The Palazzo Contarini (1908)—from the collection of the museum’s founder, software entrepreneur Hasso Plattner. museum-barberini.com

Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet, One Art Museum, Shanghai

(through January 3, 2021)

The pivotal work is one of nine Monets on view with a group of other Impressionist works and Japanese prints that influenced them. WHERE ELSE TO FIND MONET The largest Monet collection belongs to the Marmottan Museum in Paris, which in 1966 received from the artist’s son more than 100 canvases along with Monet’s collection of works by other artists. The Musée d’Orsay has nearly as many, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Art Institute of Chicago have world-class holdings contributed by Americans who were among Monet’s early and passionate patrons.