A Spirit of Adventure

Unlike other categorical spirits like bourbon or Scotch whisky, which are strictly regulated and defined by resolute parameters, the classification of amaro (or plural, amari) is largely lawless. Formal regulation is limited to just three words: bitter, sweet, liqueur. Says restaurateur Sother Teague, “if it’s got a bittering agent, a sweetening agent, and it’s alcoholic, you can call it amaro.” In 2011, Teague threw all caution to the wind and opened Amor y Amargo, an amaro- and bitters-focused cocktail bar in New York City.

Even the term “amaro,” Italian for bitter, is somewhat misleading. Beginning in the 15th century, members of monastic orders, including Franciscans, Marists, Benedictines, and Dominicans, began macerating botanicals for their medicinal uses and combining them with alcohol as a means of creating tinctures. Such practices occurred across Western Europe, but it was the Italians who passionately embraced these liqueurs centuries later, adopting them into their gastronomic cultures. Consequently, the word “amaro” is an eponym for the entire category of bittersweet liqueurs. Italians may claim that only bittersweet liqueurs made in Italy can be called amari or opine that only those designated as digestifs qualify, but the category is too broad and loosely defined to warrant these narrow classifications.

In the United States, mixology has been a welcomed gateway. Walk into most reputed craft cocktail bars today and you’ll likely find a menu peppered with concoctions that require measures of various amari. But mixology can also be challenging for the home bartender when amari are involved, since very few are interchangeable. “There’s literally dozens of ingredients in every single one of these, so it’s not so much of how is this going to play with the bourbon or tequila or rum,” says Simó, “but how is it going to play with that fortified wine that might [also] contain 40 ingredients?”

In other words, don’t try this at home without the correct ingredients. If you come across a cocktail recipe that calls for an amaro you can’t find, you’re better off waiting until you can source that specific liqueur before attempting to mix the drink because you cannot assume that an amaro produced in the same region will deliver similar flavors as the one you cannot find. With Italian amari, regional proximity doesn’t produce flavor equality. As Simó explains, Italians are fiercely loyal to their own regions and typically don’t venture outside of them when it comes to food and drink. For that reason, examples of a particular category of liqueurs will be diverse within a single region because, as Simó says, “that’s the only variety those Italians are going to get.”

Despite the enigmatic nature of the category, there’s an amaro out there to suit every taste. Here, we’ve broken them out into groups that align with the consumer’s level of experience. Whether you enjoy them neat before or after a meal, or as a complex component in a cocktail, these amari—and plenty more—will deliver a welcome moment of warmth as the cold weather rushes in this winter.

Amari for novices

Amaro Montenegro

With gentian root as its foundational bittering agent, this Italian amaro, born in Bologna in 1885, is the product of a proprietary recipe of 40 botanicals and delivers familiar flavors such as cinnamon, cloves, and sweet citrus. “This is a no-brainer for me, one that I use all the time to welcome people into the category,” says Teague. “I’ve never had it lose when someone tastes it as their first-ever amaro. Sometimes they’ll say, ‘Wow, this is amazing! You’re opening my eyes.’ At the very least they’ll say, ‘This is good.’ But no one has ever shoved this back and said, ‘I can’t do this.’”

Bonal Gentiane-Quina

Described by importer Haus Alpenz as a “spicy, earthy aperitif,” Bonal Gentiane-Quina incorporates wild plants and herbs from the foothills of the Chartreuse Mountains in southeastern France, and its prominent flavors include dried fruits, anise, fresh citrus, and cola notes. “There’s a lot going on in there, but the proof is really low,” Simó explains. “It’s a step up from a vermouth in terms of complexity and bitterness. It’s a great, accessible intro to the category of bitter, fortified wines.”

Campari

“If you’re trying to break into the world of amaro, you need to have a negroni in your life,” says Teague, referencing the classic cocktail made with gin, sweet vermouth, and Campari—an aperitivo that boasts bitter orange notes balanced by floral undertones and faint herbal character. “But I would start you off with an Americano made with small amounts of both Campari and a good, sweet vermouth, and then make it really long—flood it with seltzer—so you get to dip your toe into the bitterness that is Campari by watering it down considerably.”

Bitter Amari

Ramazzotti

At 207 years old, Ramazzotti is one of the oldest commercial amari available, and it’s an interesting example for being both approachable and complex. Bitter oranges, cardamom, clove, and myrrh are all key ingredients, though the liqueur’s full recipe includes 33 fruits, herbs, and botanicals. “It’s a kola-nut amaro, so it’s got those heavy cola notes, but it’s also got a lot of dried fruit happening,” says Teague. “If I put an ounce of this in a Collins glass with ice and fill it with seltzer, it’ll taste like Dr Pepper. It’s got that fruity quality and it’s delightful.”

Cynar

As the most popular “carciofo”-style amaro, which means its primary ingredient is artichoke, Cynar is—as you might expect—quite vegetal. Yet, despite its earthy and savory character, it finishes with a pleasant caramel sweetness. “You can lengthen it beautifully with effervescent mixers like tonic or sodas,” Simó says. “It actually likes that hint of quinine [in tonic water]. It emphasizes the vegetal notes and is one of those two-ingredient drinks that’s way more intense than you would think. Cynar also has a wonderful affinity with agave distillates. They have that shared vegetal bond, so when I’m mixing with mezcal and tequila, it’s something I’m always reaching for.”

Jägermeister

You must forget everything you’ve experienced previously when it comes to Jägermeister, especially if your first (and maybe only) encounter involved taking a colder-than-ice shot of this German bittersweet liqueur. In that scenario, your taste buds will only pick up Jägermeister’s bracing bitterness. You’ll miss the cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, licorice root, and star anise—all flavors that come to the surface when you sip the liquid at room temperature. “It’s dark, rich, and viscous,” says Teague. “However, in the world of amaro, it’s pretty sweet. And it’s got lots of familiar notes that are just compiled on top of one another. In fact, one of its biggest components is grapefruit.”

Amari for experienced palates

Sfumato Rabarbaro

Centered on Chinese rhubarb as its foundational ingredient, this unique and complex amaro presents that familiar fruity character up front and then transitions to a profound earthy smokiness that lingers on the finish. The presence of candied orange peel is easily detected; however, you may also uncover flavors of celery salt, flint, pickled herbs, and green strawberries. “I quite enjoy sipping it, but I find mixing with it really fun too, because it wants to stand out,” says Simó. “That smokiness has so much depth to it, and it allows it to hold its own in small amounts with aggressive mezcals, peaty Scotches, and overproof rums and whiskies. It can go punch for punch with the big boys.”

Opal

The genesis of this Icelandic bittersweet liqueur can be traced back to hard, chewable salted-licorice candies of the same name. For the better part of half a century, however, the company has produced a mentholated, brennivin liqueur (a form of aquavit) that showcases those same flavor profiles. Commonly called “svarti dauði,” which in Icelandic means “black death,” brennivin is Iceland’s national spirit and for many outsiders it’s an acquired taste—Opal, in particular. “It’s like eating licorice right after brushing your teeth,” says Teague. “It’s just bracing, cooling, and salted, but it’s magical. It raises eyebrows, that’s for sure.”

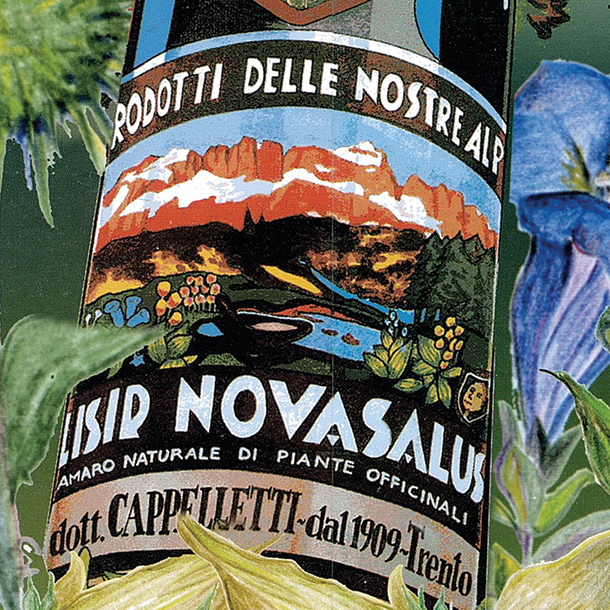

Elisir Novasalus

“Elisir Novasalus is for the person who feels like they’ve tried it all,” Teague says of this dry, Marsala wine–based amaro from Italy’s northernmost region. “The sweetening agent is the sap from a pine tree—and though sap is sticky like honey, it ain’t sweet. So, this amaro is powerfully astringent and lip-curlingly bitter. Even when I tasted it for the first time my lips backed up a little.” At only 16-percent ABV, this amaro is light in alcoholic potency, but heavy on bold and bracingly bitter flavors. As Teague acknowledges, its flavor can best be described as wood, tree bark, and forest floor.