Flower 20. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK.

Technicolor Bouquets

Flowers in all their fleeting glory sustain the vibrant work of Japanese artist AZUMA MAKOTO.

Each project exists as a sort of unfolding, a feeling that arises and then inspires new direction, all while his collaborator and childhood friend, photographer Shunsuke Shiinoki, documents the process with an exacting lens. As a creative team, they operate like punk versions of Lennon and McCartney—Makoto with his bleached blond hair and Shunsuke with his head full of dreads—each working off the other’s talents with a kind of intuitive symbiosis. They are entirely self-taught and their work is entirely driven by the flowers.

I first met Makoto five years ago in his underground design studio, a brutalist space in Tokyo that is all concrete slabs, hard angles, and temperature controls. There were stainless-steel worktables and embroidered white lab coats. The softness of the environment stemmed from Makoto’s unassuming presence and the stalks of cherry blossoms he was observing that day.

For me, the draw to his work had begun with the bright flowers he’d frozen inside of ice blocks at a Dries Van Noten fashion show in 2016. The installation was stunning in scale, breadth, and texture. It also triggered an overwhelming feeling I couldn’t quite articulate. The ice was melting. The art, disappearing. And you wanted it to stay, just as it was, even if only for a little while longer.

Makoto’s studio walls were covered back then as they are now with intricate blueprints. “I see flowers in my dreams,” he says. “[Like dreams], flowers are short-lived, so I keep a lot of notes.”

But what stayed with me most from that initial visit all those years ago was something quieter—a single photograph. Against a black backdrop, an arrangement of dahlias and delphinium could be seen actively dying. The petal colors were so saturated, they almost seemed edible or synthetic. Electric, even. And yet the flower stems could no longer hold themselves up. They hunched with the elegance of a weeping willow, forming a composition evocative of a Dutch Golden Age still-life.

Cut flowers are dying from the moment they are clipped. “That’s what this is about,” Makoto says, “noticing a flower throughout its existence, up to the end.”

X-ray Flowers. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK.

Iced Flowers. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK.

How has life amid the pandemic been? How have things changed for AMKK, the Azuma Makoto Flower Tree Research Institute?

With regard to creative expression through flowers, my activities are becoming more primitive. I have been doing these trees, for example, where I’ll take a rotted tree in the forest, shape it, and express something with it artistically. With flowers, instead of taking the ones grown in a vinyl greenhouse for maximum vitality, I’ll use weeds from the side of the road in a project. For me personally, it’s all connected to that primitive idea.

In terms of the flower shop, the number of people wanting to buy flowers has actually gone way up. With everyone staying home, people want something that is comforting, emotionally healthy—and flowers can be used for this purpose. Rather than big jobs or projects, I have experienced a kind of renewal in terms of how people and flowers relate to each other. I’ve spent all this time here in Tokyo doing not so much business-to-business, but rather a lot of flower orders for individual customers. As a florist and a flower shop owner, that has been such a great experience. It’s why I started doing this in the first place.

Is there a particular kind of flower you notice people connecting with?

It’s not a color trend per se, but I feel that everyone has been looking for flowers that have a lot of vitality. When people’s emotions are slumped, they want bright, vivid colors. When the world economy is really good and everything is going fine, people surprisingly want white or blue, for example. Cooler-colored flowers. It’s an emotional thing.

How do you structure a typical day at the flower shop?

I start at about 5 in the morning and do the watering to revive the new flowers that have come in from the market. I generally finish the flower shop’s work by midmorning, and in the afternoon I have meetings and work on preparing for future projects.

Many ancient texts describe that early-morning window as a kind of sacred time.

There is such a time when the energy is concentrated, and for flowers it’s absolutely in the morning. I don’t have scientific proof of this, but I’ve been touching flowers for 20 years and I can say this with certainty. The mood of an afternoon flower arrangement is completely different from one in the morning.

In the past, I think people knew these things instinctively. The sun goes up, and then the sun goes down and it’s time to sleep. I have a feeling that such primitive ideas are going to become essential in the future.

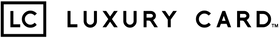

Shiki1xsandstone. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK

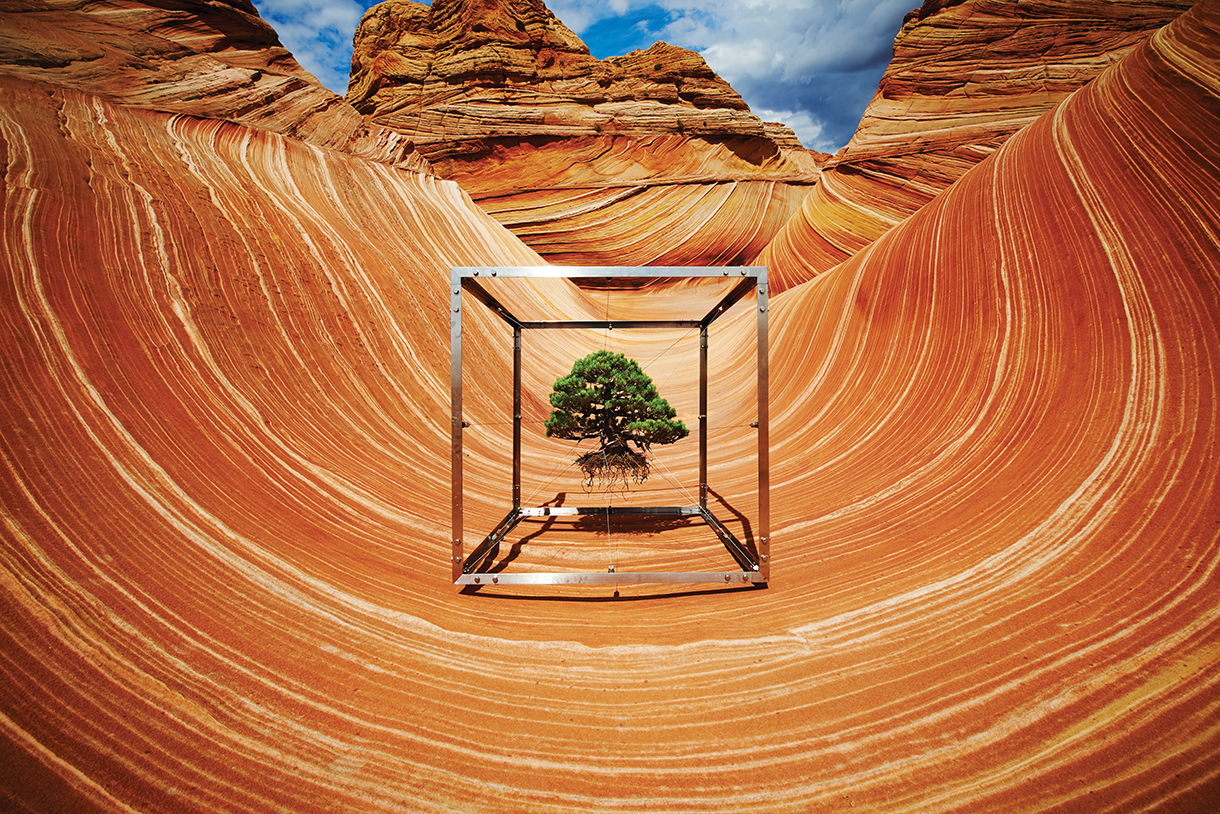

Shiki1xmonument. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK

You’ve spoken about communicating with flowers when you’re working with them. How exactly does that work?

It’s not a conversation in words … it’s a feeling. Like a secret code, a sign. I’m constantly feeling it. I feel it most strongly when I work in the morning, I feel that the code I’m receiving from the flowers is at its strongest then. That’s why I absolutely never play music in the studio when I’m creating something, because I want to take in that feeling.

Your work examines the fragility of humans and flowers. If our bodies were put through some of the forces plants endure, for example, we would tear. We would break.

Since the Earth was born it has changed and evolved over and over, but across many eons there have always been plants and flowers. It’s connected to the structure of flowers. I did a project using X-ray photography to look into why flowers have the shapes that they have. An airplane or a car, these things can be inspired by flowers. I’m actually now looking for numerical data to calculate why flowers have these shapes and why they are so strong. I have a deep interest in that, and it’s thematic for me—the structure of flowers.

It’s interesting the way science and unquantifiable realms come together in your work.

Japanese people are distinctive in this way, combining both sensory things as well as concrete things, and creating an expression out of both. I think that’s important, the extreme cutting edge combined with something in the mind or in history. Do you know the golden ratio? It’s also there in the tradition of ikebana. It’s done out of feeling, but when you put it into numbers it all comes together and makes sense.

Is sacred geometry something you’ve studied with plants and flowers?

I started from scratch. I’m still studying now. It’s also not the case that I went to ikebana school. But literature, old literature, is something that I’ve always studied. There’s such a long history of flowers. In the Mesopotamian civilization, people made offerings of flowers, and there are archeological remains of this. And it still continues to this day, the tradition of laying flowers. As long as people are alive, they will need flowers. There’s a massive history that we are repeating and creating from, and so it’s essential to make new discoveries.

Shiki1xmonument The word that comes to mind is “continuum.”

There aren’t really any people who dislike flowers, are there? Maybe they’re not interested in flowers, but nobody hates flowers. So, why? I have a theory about this. After flowers bloom, they fruit, we eat the fruit, and flowers sustain us. It’s directly related to being alive. It’s deeply connected in our consciousness, not a consciousness that we remember but a collective consciousness.

Environmentalism is at the heart of what you guys do. Brands, especially luxury brands, have not always been a part of the conversation, or they’ve been a part of it on a very surface level. But it seems like you’re introducing them to new ideas?

Recently, the luxury brands are embracing the paludarium, a device that originally was like a greenhouse concept that uses very little energy and really respects the plants without cutting them. A very big brand approached and asked me if I could make one for them, and now I’m working on a project to turn the whole store into a greenhouse. It’s fascinating! Think of greenhouses all over the world, except they’re stores, and they are selling really expensive jewelry there. It’s really exciting.

[Makoto moves through his studio to show another project]. In Japan there’s this tradition of shimenawa, a wreath usually made of straw, but I’m making one out of iron. This cultural tradition is fading away nowadays, but I want it to stay.

This sense of reverence for tradition, is this something your family imparted or is it something that developed later in life?

I grew up way out in the country [in Fukuoka], and our family always respected those traditions. In the past 20 years, though, this type of culture is suddenly disappearing. Each of these traditions has a meaning. Japan is a country with a long history, and I think that’s so valuable, so I felt that if we don’t do something now then we’ll run out of time. Incidentally, I did gain a lot of respect for that sort of thing from my parents. We were what you might call a conservative family, and so they made sure to teach me the traditions of Japan.

My father was a chef, a culinary professional. From him I learned that an artisan is someone who makes something to benefit people. My mother really loved flowers and spent a lot of time in the garden. Every day she decorated the doorway with flowers in a Japanese style. I was one of three brothers, and we were in an environment full of flowers and full of nature. I didn’t have a particular interest in flowers or desire to be a florist, but when I look back on it, I recognize that I grew up in that kind of environment. I wanted to be a musician, I always made music. Expressing myself was my life, and that was music for me. Now I express myself through flowers.

Nobody is unhappy to receive them, and music is the same—it encourages people, gives people important moments. People entrust their feelings to flowers when they can’t put them into words, and that was ultimately a big part of my decision to take this path as a flower shop owner. To give people emotion, in a supreme way. An artistic bundle of life energy, given to a person.

Burning Flowers. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK.

Growing up in the countryside, was the plan always to move to a big city?

I didn’t dream of Tokyo to be exact, but Tokyo meant access. Currently, we’re aiming to relocate to Hakone, where you can see Mount Fuji. I’d like to be a bit closer to nature.I have been able to do global work, and so I have become aware that I don’t actually need to be in Tokyo. Rather than my hometown, I’m shifting to Shizuoka. I feel energy there. I want to grow flowers. I want to be in a natural environment.

In the next 20 years, what more do you hope to accomplish?

It won’t be much different from what I’ve been doing so far—engaging with flowers and giving people new discoveries through them. I think that 20 years from now, things will be very different in every way. People will need to live in harmony with nature, there’s a hint of that happening now. I want to communicate that idea to people. I feel that’s the calling that’s been given to me. And by doing that, I think I can change the world.

COEXISTENCE 01 from “Encyclopedia of Flowers III”. All images courtesy ©Azuma Makoto ©︎Shiinoki / AMKK.