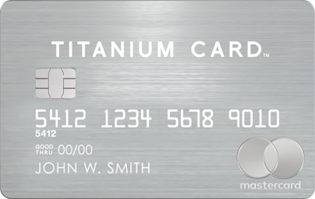

The Decomposition of a Leaf, 2022.

Beyond the Physical: Marguerite Humeau's Intertwining of Art, Science, and Spirituality

FOXP2 (Biological Showroom), Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2016

The Opera of Prehistoric Creatures –”Lucy” Autralopithecus Afarensis, -4,4-1M years ago, 2011

I observed the pulsations of a mound, like a lung inhaling and exhaling, porous, with branching passages, 2022

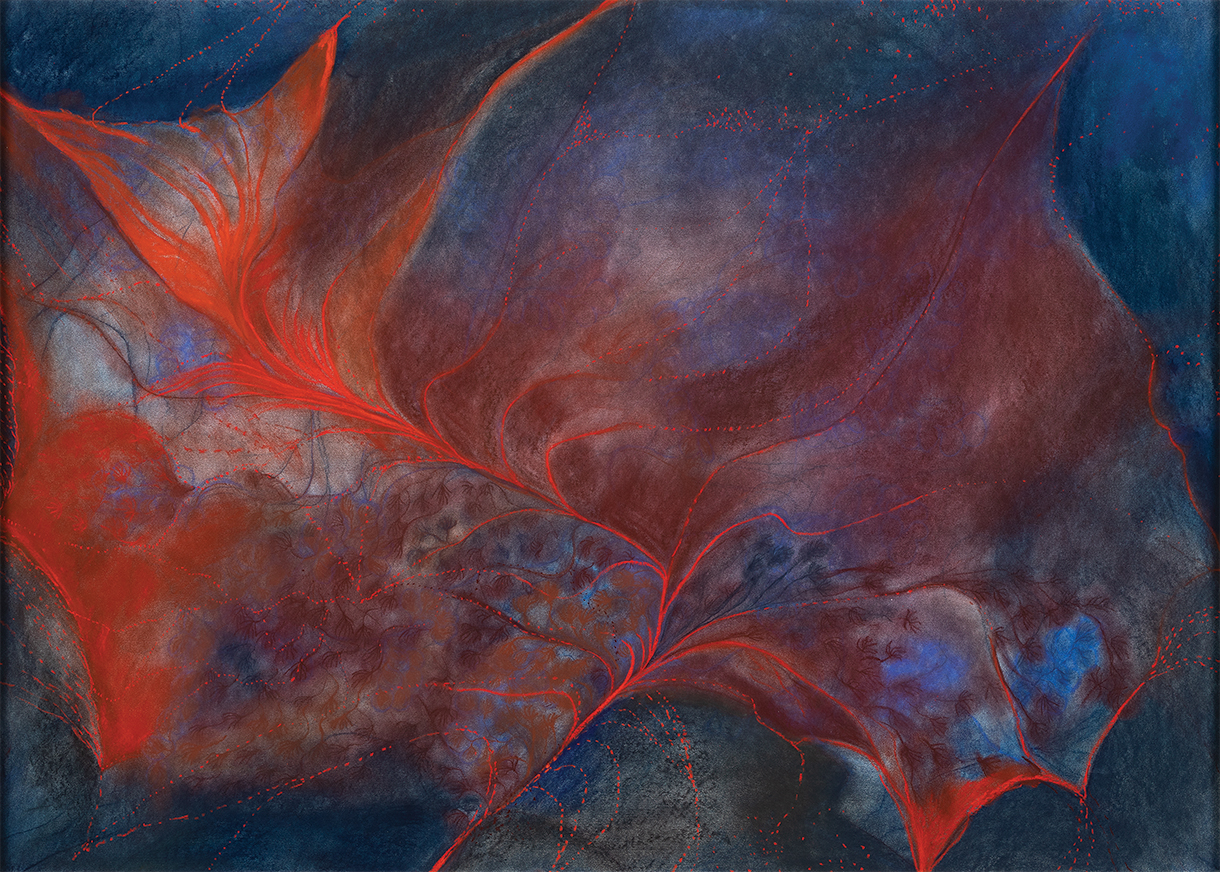

Orisons, 2023

A little more than a year ago, the conceptual artist Marguerite Humeau spent a month living and breathing this place. Orisons, her 160-acre earthwork that included 90 kinetic and interactive sculptures, was opening with Black Cube, a nomadic art gallery. “I wanted to become the land,” says Humeau, 37. “‘What if I’m a plant? What does it mean when it’s noon and there is no shade?’”

Self Portrait

The Guardian of the Fungus Garden, 2023

In the decade since MoMA found and acquired the piece for its permanent collection, Humeau’s sensuous and severe, scientific and surreal sculptural ecosystems have been exhibited in galleries and museums internationally. Her art is about humanity—about our origins; our ending; our connection with the past, the distant future, and the nebulous web of now. And it’s humanity itself that the French-born, London-based artist has increasingly harnessed to bring her expansive visions to life.

From artisans, philosophers, foragers, and wooly mammoth excavators, Humeau is something of a great-grandmother spider gifted with an ability to cultivate a web of talent who inform and push the boundaries of her creative practice. The result is often amphibious. Any given installation might include works of oil pastel, still and moving images generated with open AI, sculptures made from termite-consumed wood, blown glass, metal, latex, hand-carved onyx, and black mamba venom–infused paint. There are no limitations. The medium is the message and Humeau, the shapeshifting messenger. For Orisons, she spiraled deep into research with ornithologists, earthen architecture specialists, geomancers, clairvoyants, and mediums to conceptualize a show where the earth itself was framed as the art. The only thing she expected was the unexpected, and that’s exactly what she was met with.

“I was told there was the spirit of a woman trapped on the land in a certain area,” says Humeau. “And during the install, I found a dead bird in that spot.” Sensing the bird needed a proper burial, Humeau built a nest and enclosure using adobe bricks. “The next day, I wanted to change something and as I was opening the first brick, there was suddenly thunder in the sky. The bird had disappeared. It was gone.” Her perspective on the disappearance indirectly serves as a kind of window into her being.

“One could be rational and think: ‘Maybe someone took it.’ Which, in itself, would be interesting. It means someone had told someone about this bird—and in a way, that’s meaningful,” she says. “Or, maybe the bird could have been the spirit of the trapped woman and by burying the bird, we buried the woman, and finally she could escape. But I don’t know. I have no idea.”

There was not a drop of judgment in her voice as she spoke, only curiosity that extended in different directions like the branches of an old-growth tree. The numerous possibilities were held objectively like a scale in balance. Neither version was good nor bad. It was sand dunes and frosted mountains in a state of coexistence. Each was a part of the same greater thing. There was room for all of it.

meys with White Cube exhibition at Bermondsey, London, April 5 -May 14

I’m preparing for two projects opening in the fall and winter, so we’re deep into production. I’m doing the Gwangju Biennale, and I have a show in the United States in December.

For the biennial, I am developing a large installation to recreate a landscape of origins. We’re working with biologists in Korea who are sampling mud from a prehistoric pond called “The Ghost Pond” because it disappeared and then reappeared. They’ve been sampling mud and regrowing this whole landscape using methodology that’s accelerating the growth of bacteria. There will be inhabitants in this landscape that look almost like really small dinosaurs, but they are salamanders that never mature. In a way they are like an elixir of youth and an elixir of life because they live very long lives but physically always look like their baby selves.

They will be living in this landscape and the landscape is contained in a kind of sculpture that looks like early formations of life called stromatolites. We’ve been working with a textile designer for that. From this landscape, there come dozens of bubbles that have been blown in glass. The bubbles look like bubbles but also maybe like cells, maybe like drums. It brings up the question: How do we still carry within us the rhythms of primal, very early life?

For my show in the United States, I am thinking of a world that is posthumous and set in a desert film I’m working on. It is the first film of my life, so I’m quite daunted but really excited. It’s almost like a creation story for a world where Earth would have become so dry that the soil would start peeling off like dead skin. In a way, we would have no choice but to become nomadic bodies in flight—and maybe when this happens, our bodies also become our homes. It’s quite experimental.

The Holder of Wasp Venom, 2023

The Honey Holder, 2023

In the past couple of years I’ve started to embrace the development of forms. I used to draw a lot, and many things would have been decided beforehand. Whereas now, the way we’ve been working in the past couple of years is much more iterative. For example, this project about nomadic bodies [started] on a hike this winter, when I found a seed that looked like dead skin. It was really translucent with lots of folds that looked like wrinkles. I talked to my team about this seed, and we just really allowed for lots of free space to explore.

I think maybe three or four years ago I totally let go of something. I don’t know what happened, to be honest, but there was a moment of thinking: “OK, every show needs to be my best ever. But equally, I’m going to do this for all my life. So, each show is a new experiment. It should be playful.” I think you have to be OK with taking risks and maybe failing sometimes.

There has been a recurring element of sound and literal voice in your installations. Has this changed the way you understand your own voice?

I started with synthetic voices and exploring the boundaries of the human voice, wondering at which point does it become almost nonhuman? Is there a boundary? Then there were human voices that were trying to escape their own shells. Last year I worked with saxophonist Bendik Giske, who produced a piece of music for my show meys with White Cube. The show was about becoming collective bodies, merging with insects—and all the sculptures were made of the sum of their parts. The music was made by placing different microphones throughout the saxophone so he could play parts of the saxophone body in ways that are not normally heard. He created “voices” for all the different sculptures.

As for how it’s impacting my life? I guess strangely enough ... I’m half-deaf. I lost my hearing when I was in my twenties. I think there is a bit of a quest to find something that there was a loss of. I think sound is a powerful tool because you can really feel a strong physical presence when really, you don’t even need to feel the physical body.

Among the niche collaborators you’ve worked with, is there one who stands out as having made a significant impact on you?

I met this amazing person named Lucia Stuart. She’s a forager and a chef, and during the pandemic I asked her to help me feed myself from the London parks. She told me to intuitively choose plants that I thought I would like to eat. I would take photos and send them to her, and she would tell me: “Yes, no, yes, no.” Since then, I’ve collaborated many times with her. I will always remember this one time I went to a foraging workshop. We were on the beach, and she would pick up oysters, open them, and come like this [holds out hand directly] with the oyster and really almost put it in your mouth. I thought to myself, the connection we have with nature has been so lost that it becomes frightening. My first intuition was to feel scared that something would poison me. Or that I would pick the wrong thing. This gesture of opening the oyster and giving it to you—she was rematerializing a link or a connection that’s been lost.

“Dust” exhibition at White Cube Seoul, extraction pipes, 2024; release of gravity, 2024

“Dust” exhibition at White Cube Seoul, dead skins, 2024

“Dust” exhibition at White Cube Seoul, release of gravity, 2024

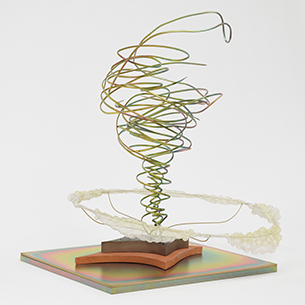

“Dust” exhibition at White Cube Seoul, the twist, 2024

I grew up in the countryside in France. My mom is a painter, so she was always quite connected to the change of seasons.

Were you always artistic?

My parents are moving, so a few weeks ago we had to go back and pack up our “teenager bedrooms” [laughs]. I saw the amount and the piles of drawings and realized I was always manically producing art. That was always at the heart of my life.

How do you choose what medium you’ll be working with?

Everything is derived from the story and the experience we are trying to craft. Is it bodily and heavy? Does it need to feel condensed? Does it need to feel like it is solid but could be liquid? Does it need to feel ethereal and like it’s going to take flight?

For example, when I was working on meys, my show about collective bodies—it just made so much sense to work with materials that are the product of collective organisms. I worked with beeswax, wood that was eaten by termites and worms, and other materials that had started a process of decomposition.

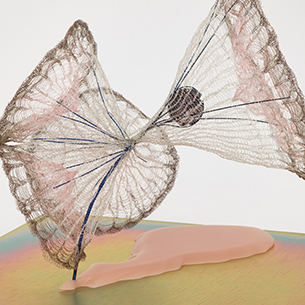

For my show DUST with White Cube Seoul that just opened, I was trying to develop this idea of space-time portals and nets, so we worked with a 3D knitter. We had to find someone who could knit sculptural forms.

Do you have a favorite myth?

I’m not sure if there’s one, but I was researching all the myths about the great flood. In almost every culture in the world, there has been a flood at some point.

My greater source of inspiration is trying to understand how it is possible that so many myths are shared across so many different civilizations. You could think of mythology as being biological, an inherent part of who we are as humans. Even if it’s in our unconscious memory, memory is matter. Every time I discover a story from a different part of the world that I didn’t know, I can connect it to something else I’ve read. I always consider how amazing it is—our connection to our early ancestors and that we all have this in ourselves. That’s where I think the power of sculpture also resides. There are forms we carry within us. When we see them, we know them somehow. We feel them.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Photo credits: Courtesy Marguerite Humeau and White Cube