23.05.62 - 07.01.71, 1962–1971, oil on canvas, 114 x 162 cm. Banque d’Images, ADAGP / Art Resource, NY

Culture

WOW ZAO

The work of Chinese-born, French-inspired abstract painter Zao Wou-Ki bridges East and West aesthetics—and shatters auction records.

by Jason Edward Kaufman

This may be the first time you have come across the name Zao Wou-Ki, but it will not be the last. One of the Chinese-born painter’s large abstract pictures recently sold for $65 million, establishing an auction record for an Asian oil painting and placing Zao, who died in 2013, among the very few postwar artists who have topped $50 million, along with Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Francis Bacon, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, David Hockney, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gerhard Richter, and Jeff Koons.

The short version of his biography is that in 1948, at the age of 28, Zao moved from his native China to Paris, where he absorbed the lessons of European modernism and developed an abstract style that merged classical Chinese aesthetics with the modernism of Europe and the United States. His landscape-like abstractions, painted in oils, watercolors, and brush and ink, were acclaimed by critics and exhibited around the world during his six-decade career.

ASTOUNDING PRICES

An artist’s death often results in a market bump, but Zao’s climb has been extraordinarily steep. In recent years, as the art world globalized, the taste for non-Western and intercultural modes of expression expanded, and interest in China increased exponentially, not only in the West. The rise of a collector class in Asia catalyzed the market for his works. Paintings that might have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars two decades ago can now top $10 million. The record sales have taken place in Asia, and auction experts report that the majority of winning bidders are from mainland China, Hong Kong, and especially Taiwan. Zao now dominates the Asian sales and annual auction turnover for his work recently exceeded that for any other postwar artist, including Americans and Europeans.

Several other factors have contributed to Zao’s posthumous ascent. In 2012, his third wife, Françoise Marquet-Zao, established the Swiss-based Zao Wou-Ki Foundation, which has promoted his legacy through scholarship and solidified his market by issuing certificates of authenticity. The artist’s estate had been contested by his son from his first marriage. In 2017 a Paris court decided in favor of Marquet-Zao, enabling her to exhibit and sell the remaining works as she saw fit. The result has been a welter of solo exhibitions at museums in Switzerland, France, and Taiwan, including major surveys at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art (2018–19), the Asia University Museum of Modern Art in Taichung, Taiwan (2017), Asia Society Museum in New York, and Colby College Museum in Waterville, Maine (2016–17).

The Asia Society show was the first US museum retrospective of Zao’s full career, and his first museum exhibition in America since the 1960s. There has been renewed interest among commercial galleries as well, including a recent show comparing him with de Kooning at Lévy-Gorvy in New York, others at Kamel Mennour Gallery in Paris and London, and a selection of large ink paintings at the powerhouse Gagosian Gallery in New York.

More than 150 museums in 20 countries own his work, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim in New York; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.; the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh; Tate Modern in London; and Centre Pompidou in Paris. His numerous accolades include the prestigious Japanese Praemium Imperiale Prize for Painting (1994), election to the French Academy of Fine Arts (2002), and being named Grand Officier of the Légion d’Honneur by President Jacques Chirac (2006). Until the rise in the 1990s of figures like Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing, and Huang Yong Ping—all of whom spent years in the West—no other postwar Chinese artist had.

The short version of his biography is that in 1948, at the age of 28, Zao moved from his native China to Paris, where he absorbed the lessons of European modernism and developed an abstract style that merged classical Chinese aesthetics with the modernism of Europe and the United States. His landscape-like abstractions, painted in oils, watercolors, and brush and ink, were acclaimed by critics and exhibited around the world during his six-decade career.

ASTOUNDING PRICES

An artist’s death often results in a market bump, but Zao’s climb has been extraordinarily steep. In recent years, as the art world globalized, the taste for non-Western and intercultural modes of expression expanded, and interest in China increased exponentially, not only in the West. The rise of a collector class in Asia catalyzed the market for his works. Paintings that might have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars two decades ago can now top $10 million. The record sales have taken place in Asia, and auction experts report that the majority of winning bidders are from mainland China, Hong Kong, and especially Taiwan. Zao now dominates the Asian sales and annual auction turnover for his work recently exceeded that for any other postwar artist, including Americans and Europeans.

Several other factors have contributed to Zao’s posthumous ascent. In 2012, his third wife, Françoise Marquet-Zao, established the Swiss-based Zao Wou-Ki Foundation, which has promoted his legacy through scholarship and solidified his market by issuing certificates of authenticity. The artist’s estate had been contested by his son from his first marriage. In 2017 a Paris court decided in favor of Marquet-Zao, enabling her to exhibit and sell the remaining works as she saw fit. The result has been a welter of solo exhibitions at museums in Switzerland, France, and Taiwan, including major surveys at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art (2018–19), the Asia University Museum of Modern Art in Taichung, Taiwan (2017), Asia Society Museum in New York, and Colby College Museum in Waterville, Maine (2016–17).

The Asia Society show was the first US museum retrospective of Zao’s full career, and his first museum exhibition in America since the 1960s. There has been renewed interest among commercial galleries as well, including a recent show comparing him with de Kooning at Lévy-Gorvy in New York, others at Kamel Mennour Gallery in Paris and London, and a selection of large ink paintings at the powerhouse Gagosian Gallery in New York.

More than 150 museums in 20 countries own his work, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim in New York; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C.; the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh; Tate Modern in London; and Centre Pompidou in Paris. His numerous accolades include the prestigious Japanese Praemium Imperiale Prize for Painting (1994), election to the French Academy of Fine Arts (2002), and being named Grand Officier of the Légion d’Honneur by President Jacques Chirac (2006). Until the rise in the 1990s of figures like Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing, and Huang Yong Ping—all of whom spent years in the West—no other postwar Chinese artist had.

12.01.2004, 2004, oil on canvas, 250 x 195 cm. Banque d’Images, ADAGP / Art Resource, NY

Untitled, 2005, oil on canvas, 130 x 97 cm. © CNAC/MNAM/Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

AFFLUENT ORIGINS

We tend not to think of Chinese artists as participants in the modern art movement. For most of the 20th century, China was an economic backwater exploited by European powers, ravaged by imperialist Japan, riven by civil war, and after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, a Communist state that became a Cold War ally of the Soviet Union. Westerners viewed the totalitarian regime with mistrust, and reduced the millennia-old civilization to a caricature consisting of Mao and his Little Red Book. As a cultural transplant, Zao embraced European life but never completely abandoned his Chinese heritage.

He was born in Beijing in 1920 and grew up in a prosperous and refined household. His father, a bank manager, descended from a Song dynasty emperor. The family moved to Nantong, a town north of Shanghai, where Zao attended school and began to draw at the age of 10. His paternal grandfather, who lived with the family, taught him classical Chinese calligraphy. It was he who suggested the name Wou-Ki, which means “no limits.”

With his father’s encouragement, in 1935 Zao enrolled in the China Academy of Art in nearby Hangzhou, where he studied brush and ink painting and European cast drawing and oil painting. He was instructed by the school’s president, Lin Fengmian, who had lived in Paris and Berlin and advocated synthesis of Chinese and modern Western art. Fleeing the Japanese invasion in 1937, the school relocated to Chongqing in central China where Zao graduated in 1941, became a teaching assistant, and had his first exhibition. He also married his girlfriend Xie Jinglan, a painter known as Lalan, with whom he had a son.

Obsessed with European art, Zao collected images from American magazines and postcards that his uncle brought back from Paris. He painted landscapes inspired by Cézanne and portraits of women in emulation of Picasso and Matisse. The Cultural Attaché of the French Embassy in China, whom Zao met in Chongqing, facilitated his participation in an exhibition of Chinese contemporary painters at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris in 1946. He urged Zao to move to Paris, and in 1948, with his father’s approval, Zao and his wife emigrated to the city where he would forge his artistic identity and remain for most of his life.

NEW LIFE IN PARIS

He rented a studio in Montparnasse next to Giacometti’s, close to the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where he studied the nude. The museums provided a crash course on art history, and his social circle grew to include the city’s cultural luminaries—musicians, poets, critics, and other abstract artists.

By 1949 he had his first solo show in Paris. He made lithographs that inspired poems by Henri Michaux, who became a great supporter. Zao and his wife bought a Volkswagen and embarked on an extensive tour of Europe. In Switzerland he encountered works by Paul Klee, whose combination of pictographic symbols and abstraction deeply influenced him. He began making blotchy atmospheric pictures overlaid with scaffoldings of calligraphic lines describing buildings, trees, boats, vessels, animals, and other motifs. Prime examples of this mode are Untitled (Golden City) (1951), a warped scene in which pictographic figures and birds populate a piazza beneath an Italianate skyline, and Black Moon (1953), a fantastic aerial view of an imaginary medieval port.

After a few years as a Klee acolyte, Zao gravitated toward the non-objective tendencies of the avant-garde. He abandoned representation and turned inward, painting fields of color embedded with linear elements based on ancient Chinese motifs from Han tomb reliefs, Shang dynasty bronzes, and oracle bones scripts. The change can be seen in Tracks in the City (1954), which renders its subject as a field of runes and angled wall-like planes, and Red Pavilion (1954), named after a classic Chinese 18th-century novel, in which black calligraphic characters float in a crimson penumbra. Zao was developing a personal pictorial symbolism that merged ancient Chinese writing and Western abstraction.

The first painting that he considered entirely abstract was Wind (1954), an expanse of leaden gray with two vertical forms, vaguely like trees, composed of mysterious black calligraphic figures. He began working on larger canvases that served as registers for his emotions. A brooding example is Red, Blue, Black (1957), in which black calligraphy is scrawled on a simmering blood-red field. Referring to this period in his autobiography, published in 1988, Zao recalled, “Still lifes, flowers, and animals disappeared. I was attempting to reveal something imaginary with signs, inscribed on almost monochromatic backgrounds … Then, little by little, signs turned into forms, backgrounds into space.”

We tend not to think of Chinese artists as participants in the modern art movement. For most of the 20th century, China was an economic backwater exploited by European powers, ravaged by imperialist Japan, riven by civil war, and after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, a Communist state that became a Cold War ally of the Soviet Union. Westerners viewed the totalitarian regime with mistrust, and reduced the millennia-old civilization to a caricature consisting of Mao and his Little Red Book. As a cultural transplant, Zao embraced European life but never completely abandoned his Chinese heritage.

He was born in Beijing in 1920 and grew up in a prosperous and refined household. His father, a bank manager, descended from a Song dynasty emperor. The family moved to Nantong, a town north of Shanghai, where Zao attended school and began to draw at the age of 10. His paternal grandfather, who lived with the family, taught him classical Chinese calligraphy. It was he who suggested the name Wou-Ki, which means “no limits.”

With his father’s encouragement, in 1935 Zao enrolled in the China Academy of Art in nearby Hangzhou, where he studied brush and ink painting and European cast drawing and oil painting. He was instructed by the school’s president, Lin Fengmian, who had lived in Paris and Berlin and advocated synthesis of Chinese and modern Western art. Fleeing the Japanese invasion in 1937, the school relocated to Chongqing in central China where Zao graduated in 1941, became a teaching assistant, and had his first exhibition. He also married his girlfriend Xie Jinglan, a painter known as Lalan, with whom he had a son.

Obsessed with European art, Zao collected images from American magazines and postcards that his uncle brought back from Paris. He painted landscapes inspired by Cézanne and portraits of women in emulation of Picasso and Matisse. The Cultural Attaché of the French Embassy in China, whom Zao met in Chongqing, facilitated his participation in an exhibition of Chinese contemporary painters at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris in 1946. He urged Zao to move to Paris, and in 1948, with his father’s approval, Zao and his wife emigrated to the city where he would forge his artistic identity and remain for most of his life.

NEW LIFE IN PARIS

He rented a studio in Montparnasse next to Giacometti’s, close to the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where he studied the nude. The museums provided a crash course on art history, and his social circle grew to include the city’s cultural luminaries—musicians, poets, critics, and other abstract artists.

By 1949 he had his first solo show in Paris. He made lithographs that inspired poems by Henri Michaux, who became a great supporter. Zao and his wife bought a Volkswagen and embarked on an extensive tour of Europe. In Switzerland he encountered works by Paul Klee, whose combination of pictographic symbols and abstraction deeply influenced him. He began making blotchy atmospheric pictures overlaid with scaffoldings of calligraphic lines describing buildings, trees, boats, vessels, animals, and other motifs. Prime examples of this mode are Untitled (Golden City) (1951), a warped scene in which pictographic figures and birds populate a piazza beneath an Italianate skyline, and Black Moon (1953), a fantastic aerial view of an imaginary medieval port.

After a few years as a Klee acolyte, Zao gravitated toward the non-objective tendencies of the avant-garde. He abandoned representation and turned inward, painting fields of color embedded with linear elements based on ancient Chinese motifs from Han tomb reliefs, Shang dynasty bronzes, and oracle bones scripts. The change can be seen in Tracks in the City (1954), which renders its subject as a field of runes and angled wall-like planes, and Red Pavilion (1954), named after a classic Chinese 18th-century novel, in which black calligraphic characters float in a crimson penumbra. Zao was developing a personal pictorial symbolism that merged ancient Chinese writing and Western abstraction.

The first painting that he considered entirely abstract was Wind (1954), an expanse of leaden gray with two vertical forms, vaguely like trees, composed of mysterious black calligraphic figures. He began working on larger canvases that served as registers for his emotions. A brooding example is Red, Blue, Black (1957), in which black calligraphy is scrawled on a simmering blood-red field. Referring to this period in his autobiography, published in 1988, Zao recalled, “Still lifes, flowers, and animals disappeared. I was attempting to reveal something imaginary with signs, inscribed on almost monochromatic backgrounds … Then, little by little, signs turned into forms, backgrounds into space.”

June-October 1985 Triptych, 1985, oil on canvas, 280 x 1,000 cm. Banque d’Images, ADAGP / Art Resource, NY

PUBLIC SUCCESS AND PRIVATE TROUBLES

Zao was gaining recognition, in 1951 signing on with the prominent Galerie Pierre, known for exhibiting Picasso, Miró, Giacometti, and the Surrealists, and soon was showing in group shows in New York where his work was enthusiastically received by collectors. He was included in the Cincinnati Art Museum’s print biennials and the Carnegie Museum of Art’s contemporary art triennials, and major institutions acquired his work. He was only 34 when the Cincinnati Art Museum held his first US retrospective in 1954; that same year, he was featured in a Life magazine piece titled, “Artist from East is Hit in West.” He would have a second at SFMOMA in 1968, the year H.H. Arneson, director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, included him in History of Modern Art, which became a standard college textbook for decades.

Meanwhile, his marriage collapsed. In 1957, Xie Jinglan divorced him and he left for a four-month stay with his younger brother, an MIT-trained engineer who lived in Montclair, New Jersey. He frequented New York, familiarized himself with Abstract Expressionism, and met Franz Kline, Hans Hoffman, and other leading American painters. He embarked with the French artist Pierre Soulages on a trip across the United States to Hawaii and Japan, then proceeded on his own to Hong Kong where he met May-Kan Chan, a movie starlet known as May Choo, whom he married in 1958 before returning to Paris.

His first solo show in New York took place in 1959 at the Samuel Kootz Gallery, a proponent of Abstract Expressionism. The gallery closed in 1966, and Zao would not show again in Manhattan until Pierre Matisse Gallery mounted an exhibition in 1980, with a catalog introduction by the artist’s friend, the Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei, whom he first met in 1951.

Zao continued to exhibit in Paris, Geneva, and elsewhere in Europe, often with catalogs written by notable critics. And he bought a Paris warehouse and converted it into a large studio that allowed him to paint on a grander scale. In 1960 the French government invited him to participate in the Venice Biennale (the same year that Franz Kline represented the United States), though he would not become a French citizen until 1964. After a major retrospective at the Folkwang Museum in Essen in 1965, he contributed to the French pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, and in 1969 he had another painting retrospective, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Montreal. But his momentum was again derailed by trouble in his personal life, this time even more tragic.

May-Kan Chan had launched a career as an abstract sculptor, but she suffered from mental illness and depression. She died in 1972; soon after, Zao retreated to Shanghai to visit his ailing mother. He had not been back to China since 1948, and the son he had left there was now 28. When he returned to France, he painted In Memory of May (1972), a sprawling somber abstraction with black forms floating against a fiery orange-yellow expanse tinged with light. His situation brightened the following year when he met Françoise Marquet, a curator at the museums of the City of Paris. They married in 1977, commencing a 36-year relationship that provided the domestic calm he needed to paint.

Zao was gaining recognition, in 1951 signing on with the prominent Galerie Pierre, known for exhibiting Picasso, Miró, Giacometti, and the Surrealists, and soon was showing in group shows in New York where his work was enthusiastically received by collectors. He was included in the Cincinnati Art Museum’s print biennials and the Carnegie Museum of Art’s contemporary art triennials, and major institutions acquired his work. He was only 34 when the Cincinnati Art Museum held his first US retrospective in 1954; that same year, he was featured in a Life magazine piece titled, “Artist from East is Hit in West.” He would have a second at SFMOMA in 1968, the year H.H. Arneson, director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, included him in History of Modern Art, which became a standard college textbook for decades.

Meanwhile, his marriage collapsed. In 1957, Xie Jinglan divorced him and he left for a four-month stay with his younger brother, an MIT-trained engineer who lived in Montclair, New Jersey. He frequented New York, familiarized himself with Abstract Expressionism, and met Franz Kline, Hans Hoffman, and other leading American painters. He embarked with the French artist Pierre Soulages on a trip across the United States to Hawaii and Japan, then proceeded on his own to Hong Kong where he met May-Kan Chan, a movie starlet known as May Choo, whom he married in 1958 before returning to Paris.

His first solo show in New York took place in 1959 at the Samuel Kootz Gallery, a proponent of Abstract Expressionism. The gallery closed in 1966, and Zao would not show again in Manhattan until Pierre Matisse Gallery mounted an exhibition in 1980, with a catalog introduction by the artist’s friend, the Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei, whom he first met in 1951.

Zao continued to exhibit in Paris, Geneva, and elsewhere in Europe, often with catalogs written by notable critics. And he bought a Paris warehouse and converted it into a large studio that allowed him to paint on a grander scale. In 1960 the French government invited him to participate in the Venice Biennale (the same year that Franz Kline represented the United States), though he would not become a French citizen until 1964. After a major retrospective at the Folkwang Museum in Essen in 1965, he contributed to the French pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, and in 1969 he had another painting retrospective, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Montreal. But his momentum was again derailed by trouble in his personal life, this time even more tragic.

May-Kan Chan had launched a career as an abstract sculptor, but she suffered from mental illness and depression. She died in 1972; soon after, Zao retreated to Shanghai to visit his ailing mother. He had not been back to China since 1948, and the son he had left there was now 28. When he returned to France, he painted In Memory of May (1972), a sprawling somber abstraction with black forms floating against a fiery orange-yellow expanse tinged with light. His situation brightened the following year when he met Françoise Marquet, a curator at the museums of the City of Paris. They married in 1977, commencing a 36-year relationship that provided the domestic calm he needed to paint.

14.09.2000, 2000, oil on canvas, 96 x 104 cm. Banque d’Images, ADAGP / Art Resource, NY

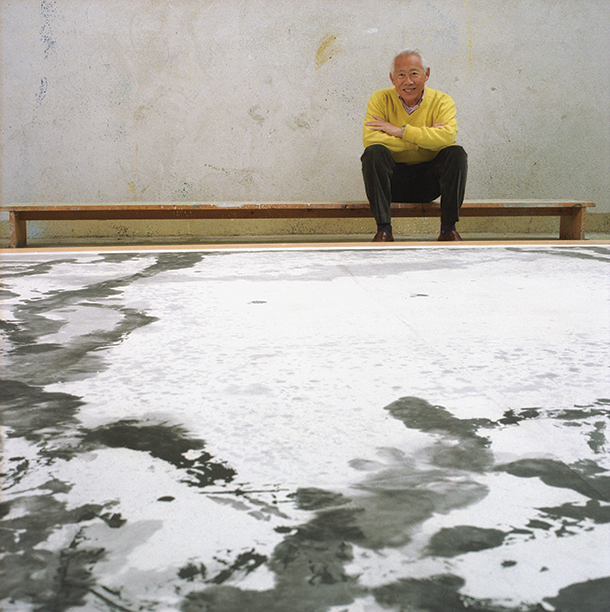

Zao Wou-Ki in his studio. Micheline Pelletier / Getty Images

EXPLOSION OF COLOR

He moved into a larger studio in the countryside where he produced monumental works, many of them triptychs reminiscent of Asian folding screens and medieval motifs. He wanted them to be immersive, a “true projection of one’s body” that reflected the movement that went into their making. References to calligraphic script became looser and illegible as he strove to develop his own “characters and language, or a system of symbols.” An example is the 17-foot-long panorama 27.08.82 – Triptych (1982), in which yellow paint extends diagonally across areas of dark blue, suggesting a sandy shoreline or a hazy vista over mountains, autumnal forests, and the sea.

In 1980 he was appointed professor at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where he would teach until 1984. The Grand Palais mounted his first Paris museum show in 1981, and sent it to seven museums in Japan. In 1983 the Chinese Culture Ministry organized his first major show in his native country, presented at the National Museum in Beijing and the Hangzhou Academy of Fine Art. Two years later he and his wife were invited to teach for a month at the Hangzhou Academy, his alma mater. In his remaining decades, Zao’s works became more luminous and chromatically vibrant, and landscape allusions became more pronounced. One of his most explicit, Homage to Claude Monet, February–June 91 – Triptych (1991), borrows the impressionist’s distinctive mauve palette to depict the natural arch off the coast of Étretat, a landmark that features in many Monet paintings.

Zao abandoned oil painting in 2008 and turned to the less physically demanding medium of watercolor. In 2011 he and his wife moved to Dully, Switzerland, where he worked until his death in 2013 at 93. He was buried, according to his wishes, in Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

LEGACY Zao is best known for his imposing paintings, but he also illustrated many volumes of poetry, created costumes and sets for ballets, and designed porcelains for Sèvres and Atelier Bernardaud as well as tapestries for the Aubusson and Gobelins factories. He also designed mosaics for sites in France, a ceramic mural for the Lisbon metro, and 14 stained-glass windows for a priory on the Loire near Tours. He completed paintings to decorate building projects, including many for his architect friend I.M. Pei. The $65 million work, June–October 1985 (1985)—a triptych more than 33 feet wide—was a commission for Pei’s Raffles City in Singapore, which also included works by Ellsworth Kelly and Kenneth Noland.

Despite his flourishing career, Zao, like most Asian artists, has not been fully integrated into the Euro-American canon of mid-century abstraction. Many Abstract Expressionists in New York and Art Informel painters in Europe were expatriates, but very few were from Asia, and the question of whether Zao was Chinese or Western, coupled with the impact of Eastern aesthetics on his art, has shunted him slightly outside the mainstream. Art historians have been revising the canon to embrace abstract art from Asia (e.g., the Gutai artists of Japan) and the Asian diaspora. Zao is increasingly regarded not as an outlier, but as a full-fledged member of the postwar School of Paris. Zao himself did not see Eastern and Western painting as separate, but as comparable forms of painting that he sought to meld to form a universal language. Regardless of his status in the West, with the Asian collectors fueling his skyrocketing market, Zao Wou-Ki’s place in art history is assured.

He moved into a larger studio in the countryside where he produced monumental works, many of them triptychs reminiscent of Asian folding screens and medieval motifs. He wanted them to be immersive, a “true projection of one’s body” that reflected the movement that went into their making. References to calligraphic script became looser and illegible as he strove to develop his own “characters and language, or a system of symbols.” An example is the 17-foot-long panorama 27.08.82 – Triptych (1982), in which yellow paint extends diagonally across areas of dark blue, suggesting a sandy shoreline or a hazy vista over mountains, autumnal forests, and the sea.

In 1980 he was appointed professor at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where he would teach until 1984. The Grand Palais mounted his first Paris museum show in 1981, and sent it to seven museums in Japan. In 1983 the Chinese Culture Ministry organized his first major show in his native country, presented at the National Museum in Beijing and the Hangzhou Academy of Fine Art. Two years later he and his wife were invited to teach for a month at the Hangzhou Academy, his alma mater. In his remaining decades, Zao’s works became more luminous and chromatically vibrant, and landscape allusions became more pronounced. One of his most explicit, Homage to Claude Monet, February–June 91 – Triptych (1991), borrows the impressionist’s distinctive mauve palette to depict the natural arch off the coast of Étretat, a landmark that features in many Monet paintings.

Zao abandoned oil painting in 2008 and turned to the less physically demanding medium of watercolor. In 2011 he and his wife moved to Dully, Switzerland, where he worked until his death in 2013 at 93. He was buried, according to his wishes, in Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

LEGACY Zao is best known for his imposing paintings, but he also illustrated many volumes of poetry, created costumes and sets for ballets, and designed porcelains for Sèvres and Atelier Bernardaud as well as tapestries for the Aubusson and Gobelins factories. He also designed mosaics for sites in France, a ceramic mural for the Lisbon metro, and 14 stained-glass windows for a priory on the Loire near Tours. He completed paintings to decorate building projects, including many for his architect friend I.M. Pei. The $65 million work, June–October 1985 (1985)—a triptych more than 33 feet wide—was a commission for Pei’s Raffles City in Singapore, which also included works by Ellsworth Kelly and Kenneth Noland.

Despite his flourishing career, Zao, like most Asian artists, has not been fully integrated into the Euro-American canon of mid-century abstraction. Many Abstract Expressionists in New York and Art Informel painters in Europe were expatriates, but very few were from Asia, and the question of whether Zao was Chinese or Western, coupled with the impact of Eastern aesthetics on his art, has shunted him slightly outside the mainstream. Art historians have been revising the canon to embrace abstract art from Asia (e.g., the Gutai artists of Japan) and the Asian diaspora. Zao is increasingly regarded not as an outlier, but as a full-fledged member of the postwar School of Paris. Zao himself did not see Eastern and Western painting as separate, but as comparable forms of painting that he sought to meld to form a universal language. Regardless of his status in the West, with the Asian collectors fueling his skyrocketing market, Zao Wou-Ki’s place in art history is assured.